Before the Internet was born in 1983, computer networks lacked a standard method of communicating with one another. In the years since — as online communications have grown interwoven with our daily lives and revolutionised the world we live in — there remains a crucial thing we still don’t have a standardised way of talking about in the digital world: you.

Without a standardised way of identifying people online, websites began to use local accounts with usernames and passwords. You likely have several of these that you rely on in your daily life: your Amazon account, your email account, your Netflix account. These sites also began storing usage information, personal data and data about the user obtained through 3rd party sources in the user account. This approach created so-called siloed identities.

As the internet has grown to encompass everything from your private inbox to your grocery orders, your workout regimen and your finances, your personal data is now collected and stored in dozens of places outside your control. You — the digital you that is — are a string of accounts where third parties hold your information on their servers.

This creates big problems. Your data resides in silos that are potentially vulnerable to hackers, data leakage and other privacy breaches. Just ask the 338 million customers of Marriott Hotels whose personal information, including passport numbers, were leaked between 2014 and 2018. In 2020 alone, the number of personal records compromised in data breaches grew 141 percent to 38 billion, according to security firm Risk Based Security (RSB). The other problem is that the usage of this data, even if it is secure, cannot be controlled — the user even doesn’t know what is stored where and has no direct access. Not to mention that this approach requires a separate account for every service you use, leaving you with dozens or even hundreds of passwords and logins (remember, you should never reuse a password!), multiplying the spread of your personal data across the internet and contributing to a less-than-satisfactory user experience. What’s more, this situation leaves internet users vulnerable to phishing and other scams that trick people into giving away their personal data.

With the rise of internet giants like Google and Facebook came the idea of federated identity. That’s when third parties allow you to log in to their site or app using, for example, your Gmail account. If you go to a website and use the “sign in with” functionality, known as “single sign-on”, you’re using a federated identity — Google or Facebook are playing the role of identity provider. In such a setup, the multi-account problem may have been solved, but new, serious problems arise. The companies that dominate the federated identity space, basically acting as middlemen for your digital existence, have huge economic incentive to collect as much data about your online interactions as possible — and mine it for profit. Google, for example, has been accused of secretly tracking its own users in Europe, and was fined for illegally harvesting data from children in the US. A less obvious issue is that the providers of single sign-on services also have control over where you are allowed to use your identity and can potentially deny its usage according to their will, be it economic interest, opaque ethical principles or governmental pressure. Twitter can ban you forever, Instagram can close your account, Facebook can wipe your page. You could say that they control your digital existence.

Thankfully, a better way is emerging. It’s a third kind of online identity where your personal data is neither strewn across an inefficient patchwork of silos nor controlled by a big company that mines your personal data for money.

It’s called self-sovereign identity (SSI).

What is SSI?

Self-sovereign identity is the next major step in the evolution of digital identity. It closes the gap on inefficiencies and privacy concerns around the ways you make yourself known online by putting you in control.

First, here’s the theory behind it.

Basically, SSI means a person, or an organisation, completely owns, controls and manages their identity online. You are your own identity provider — there is no one else who can claim to “provide” your identity for you because it’s intrinsically yours.

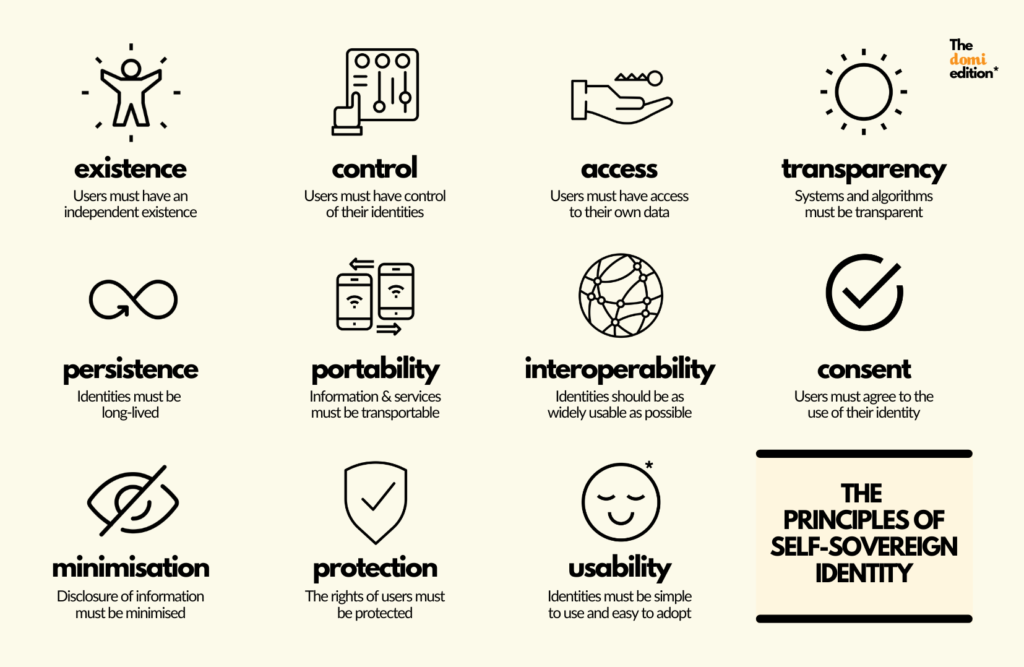

In a more formal way we can say that SSI follows 10 key principles, as first outlined by Christopher Allen:

- SSI provides an independent existence and absolute control for its users, who hold the access to their own data. That means no intermediaries owning or sifting through your data: it belongs to you.

- SSI is transparent (so that you can understand any system or algorithm involved), interoperable (so it integrates well with other systems) and portable (meaning no vendor or device lock-in).

- SSI offers persistence (the identities will last for as long as you want them to last… no need to worry about Facebook deleting your Instagram account) and protection (erring always on the side of protecting individuals’ freedoms and rights).

- SSI prioritises consent (users must always agree to how their identity is being used — whether that’s to disclose or restrict data) and minimisation (you should only disclose the data that you need to, supporting privacy as much as you can.)

To this practical list, Domi adds an 11th principle of our own:

- SSI values usability — it’s easy to use, adopt and understand. There are no complex bells and whistles, just the means to share and use the information you want, when you want, and it’s easy to carry around with you.

From the user perspective, practical SSI looks like this:

As the user, you possess a digital identity wallet which stores the data related to your identity and interacts with other SSI-enabled systems. The wallet can be in the form of an app on your mobile phone or a web-based service or, often, a combination of both.

Your personal data is stored in the wallet in the form of verifiable credentials, rather than on centralised servers. It’s kept under the user’s sovereign control and literally in the user’s possession. A verifiable credential itself is a representation of data which is cryptographically tamper-proof and traceable to its origin (more on that later).

What sort of personal data can be stored in the identity wallet? Any statement about you that can be represented digitally! This could include digital representations of personal ID cards, education diplomas, login credentials, property deeds, corporate badges, vaccination passports, COVID-19 test results, any transaction records and much, much more. Using the wallet, you can selectively present some of these credentials to an interested third party, either some of the time or all of the time. You can record your consent to share data with others, and easily facilitate that sharing. Your data is persistent and not reliant on any single third party to be stored or forwarded.

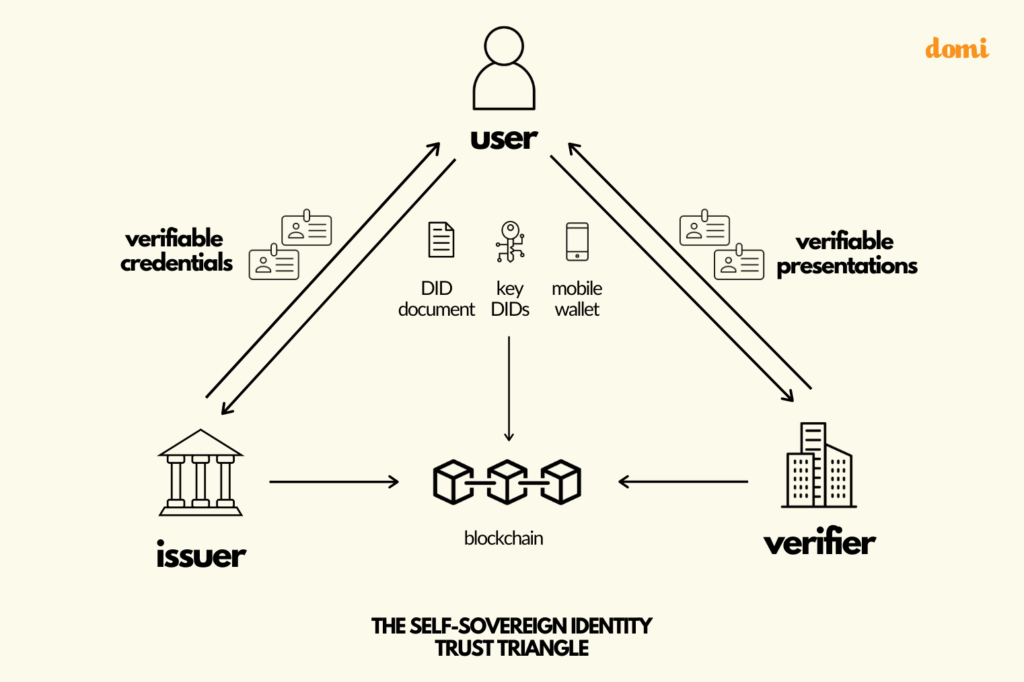

Now that we have the basic components, let’s look at the interactions they enable. In the below diagram, we have a mental model for how identity can be managed in a way that delivers on the SSI principles. It is known as the SSI Trust Triangle.

Let’s walk through this diagram step by step.

An issuer makes claims or assertions about a user. These claims are bundled together into verifiable credentials and given to the user, who stores them in their digital wallet. From there, they can decide which verifiers they want to present these credentials to.

For example, let’s say the issuer in this case is a university. The assertion they want to make about you is that you’re a graduate and that you have an MBA. So they issue a verifiable credential that you can store in your identity wallet. Now, let’s say you’re applying for a job at a financial agency. As part of your application, you’re able to prove that you have an MBA by making your credential visible to the company you’re applying to. Note that the verifier — in this case the prospective employer — does not need to contact the university to confirm the authenticity of the diploma credential. Conversely, neither the university, nor anyone else, will know which companies you are applying to.

Many real-world business interactions involve a similar flow of data.

Need a fishing license? Rather than go to a government office, with SSI you could apply using a digital driver’s license. Want to sign up for an industry conference? Use a digital work ID issued by your employer. Want to rent a flat? Confirm your ID, your proof of solvency and your employment status to your new landlord by presenting the relevant credentials in your wallet.

If you were looking carefully at the diagram you might have noticed that it also has “blockchain” in it — we haven’t mentioned that yet! Read on to learn the role distributed ledger technologies play in SSI and why they work so well together.

What’s the Technology Behind SSI?

SSI relies on modern cryptography and decentralisation to make the things described above work.

The core idea is to give users free, unique, machine-readable, user-controlled, persistent and anonymous identifiers that are decoupled from the “personal data” about the user they “identify”. These are called decentralised identifiers, or DIDs. This might sound intimidatingly jargonistic, but the idea of identifiers is of course not new — email addresses, phone numbers, profile IDs and all sorts of other sensitive numbers have a long tradition of being (mis-)used for such purposes. The difference is that they are neither free, persistent, anonymous nor user-controlled.

DIDs can not only be generated for people, but also for organisations, objects, digital documents and more. Every participant in the SSI ecosystem needs at least one, but you can also have more than one DID in the same way that you might have one email address for work and one for personal use. Each DID is cryptographically linked to a secret key that only the DID owner knows, along with a corresponding public key that other users can use to verify claims made by the DID owner. Aside from this, DIDs are anonymous: they don’t contain or reveal any information about their owner.

The blockchain is used to perpetuate this linkage in a way that guarantees that the data associated to the link can be changed by the owner of the DID, cannot be maliciously manipulated and persists forever. (NB: this is of course based on the assumption that a decentralised structure with many autonomous nodes will not go down, as a one single company could. There are also SSI architectures that work without distributed ledgers.)

The second pillar of SSI is the concept of verifiable credentials, or VCs, which can be thought of as a “file format” for storing the claims about an entity which guarantees the authenticity and integrity of the data. They also come with useful features like selective disclosure of claims, Zero Knowledge Proofs, and semantic overlays that do not have analogue alternatives. For now, though, all you need to remember is that a VC contains real-world relatable data about a thing or person — the credential subject — and that it is linked to the DIDs of the issuer and the subject and is tamper-proof.

The main function of your identity wallet is to manage the user’s private keys, store VCs about the user securely and enable safe communication with other identity wallets, in order to exchange VCs and data derived from them in a way that protects your privacy.

Whenever you need to disclose information to a third party, your wallet will let you pick the relevant data attributes from different credentials and combine them with the DIDs of the corresponding issuers, as well as your own DID and a cryptographic signature. This is called a verifiable presentation (VP). From here, the VP can be transferred to the verifier, who, based on the cryptographic signature in the VP, is able to independently verify two things:

- The data contained in the issuer’s claims have not been changed, and

- the person who presented the VP is the same person about whom the issuer originally made the claim.

Of course, this is just an overview and does not cover important aspects such as security, revocation of credentials and governance structure. In the meantime, the Domi Labs and the SSI community continue to explore and develop these topics. Expect blog posts on them soon!

The Future of Your Identity

It won’t happen overnight, but the move away from conventional siloed and federated identities is already underway, giving people more control over their lives as well as more convenience.

Already, SSI projects exist that:

- Help refugees prove their identities and credentials in their new homeland.

- Onboard new customers at major financial institutions.

- Allow you to present Covid-19 tests and vaccination records when you travel.

The possibilities for the technology are virtually endless. Policymakers see this, too: The European Union is developing its own European Self-Sovereign Identity Framework (ESSIF), and has invested in companies developing SSI projects and platforms.

The benefits of adopting SSI are also clear: increased privacy, fewer data breaches, and more efficient administration of business and government, which helps in the process of wealth creation. At this point, it’s no longer a matter of if, but when.

Interested in joining the Domi team? We’re hiring! Take a look at our open positions.